A website dedicated to athletics literature / The Athlete Vol., No.1.

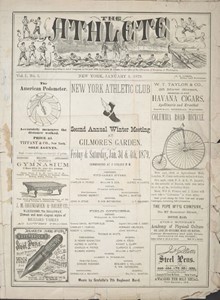

The Athlete Vol., No.1.

D. D. Comes. The Athlete Vol., No.1., 1879

The author:

Daniel D. Comes is listed as the editor and publisher of The Athlete and its numbering seems to suggest that it was intended to be the first in a series, rather like a magazine; in fact it was the programme of an athletics meeting put on by New York Athletic Club. Comes published it from 2 Courtlandt Street, New York (on the corner of Courtlandt and Broadway), and he had set himself up as a publisher of athletics material and was about to publish the Rules for the Government of Athletics Meetings as a pocket book, bound in cloth, and gilt.

No price is printed on The Athlete, and it may well have been distributed free. It seems that Copes had taken the publishing responsibility for the programme from NYAC and raised the money from advertising to cover his costs, hoping to establish himself as an athletics publisher, with money to be made, perhaps, at some future date. He was also associated with the military, and three years later was acting Quartermaster of the Veteran Battalion of the Twenty-Second Regiment; but he doesn’t seem to have had a high profile as either an athlete or a publisher.

The place of Comes' “The Athlete” in the history of Athletics literature:

The Athlete Vol., No.1 is the programme for the first day of a two-day winter athletics meeting at Gilmore’s Garden in the heart of New York in January 1879. It helps us to get our bearings by knowing that five months later Gilmore’s Garden changed its name to Madison Square Garden, a major New York venue, so this was a significant undertaking by the NYAC, and was an attempt to take athletics to the people and make it a commercial success - in short, to make it show biz. It was not the first attempt to do so - the first was exactly one year earlier in January 1878, also staged by the New York Athletic Club, and also in Gilmore’s Garden. This then, was The Second Annual Winter Meeting, and that is how it was described. It was earlier advertised as being “indoors”, but Gilmore’s Garden is invariably described as an outdoor venue, so it was probably an “indoor” venue that had no roof; but, as the track was only 220yds long, this was a hybrid meeting, and the tight bends would have been unfamiliar to the athletes, and would have affected their times. The nature of the surface is unknown. The indoor/outdoor nature of the event is also important because the temperature in the evening in early January in New York is cold, very cold.

New York Athletic Club had been formed in September 1868, and so had a decade of activity and development behind it. The NYAC was said to have put on the first Track and Field meet in America, at which, it was said, the first pair of spiked shoes were seen in New York, and to have built the first cinder track in America. We need to be careful of such Headline History however - there are other claimants to the title of first athletic club in North America (Montreal), and in the United States, San Francisco and New Jersey also had very early athletics clubs, and athletic-type competitions (running, throwing and jumping) had been going on in America for many years. Indeed, Sir Francis Nicholson arranged athletic games in Virginia in 1691. Nevertheless, the NYAC was important and innovative, and its activities were very influential.

A winter meeting in the heart of New York was part of its innovative and expansive programme. The NYAC, however, was not a Track & Field club per se; it was a sports club, founded by William B. Curtis and John C. Babcock from the worlds of rowing and boxing, and so, not surprisingly, the First Winter Meeting featured boxing as well as running, hurdling, and tug-of-war; and unfortunately it was the boxing that got the newspaper headlines then. Boxing started the programme, but it certainly wasn’t genteel sparring and soon a man lay “quivering on the platform . . . utterly senseless.” “Felled like an ox.” The women in the crowd did not like it and Police Capt Williams, in whose precinct the event was taking place, said it would not be permitted; and so A.H. Curtis, secretary of the NYAC, had to hurriedly issue a statement saying that there would be no more sparring at the Winter Meeting. So, the following year, in January 1879, the NYAC were looking for a new image, and a chance to redeem themselves in the eyes of the public – and, as we can see, no boxing (or sparring) events were advertised on the programme for the Second Annual Winter Meeting.

The NYAC, however, had a considerable task in front of them. Track & Field was a new sport in the USA and had not yet produced any stars or household names; but they had to somehow get a crowd into Gilmore’s Garden, and New Yorkers had become used to some very exciting, and sometimes bizarre, events to lure them through Gilmore’s Garden’s doors. In 1878 a Congress of Beauty and Culture at Gilmore's Garden advertised for 1,000 women under 40 years of age, 500 misses, and 500 boys, and when it was staged it was described as a shameful and unseemly exhibition; but it attracted a large, raucous crowd. There was a lacrosse match in which a New NY team took on a team of Canadian Indians in front of a large crowd of excited spectators, a British menagerie and circus that played to capacity crowds, six-day walking matches, baby shows, dog shows, and so on - all heavily promoted. It could even be converted into a skating rink.

How were the NYAC going to attract a crowd on a Friday night with amateur athletes none of whom was well known? But amateur athletics was a new fad and was capturing the spirit of the age. It was an English cultural import, and fashionably popular, and the Amateur Athletic Club in London had created the pattern that others were to follow; in 1866 the AAC had adopted a multi-pronged approach:- an annual Championship Meeting - an autumn Handicap Meeting - the creation of training facilities for its members - and the establishment of Laws to govern competition. The NYAC followed this pattern faithfully, and this meeting in New York in January was their Handicap Meeting.

However, the New York Athletic Club was not only about imitation. They were certainly inspired by the AAC in England and acknowledged their debt to it, and in the “editorial”, Daniel Comes wrote -

England, commonly known as our Mother Country, is pre-eminently so in athletics. She taught us all these sports,

and with each game we naturally borrowed its laws.

They might have been inspired by the AAC in England, but they were not limited by it. Comes went on to say that the AAC’s Laws were incomplete and that the New York Athletic Club had compiled its own -

An examination of these two codes will show that the American is founded on the English, and their fundamental

principles are the same. The American compilation is an amplification and improvement of the English model.

The defect of the English laws is not incorrectness, but incompleteness, and they are really but the skeleton or

framework on which the New York Athletic Club have built up their more comprehensive and definitive code.

This was a turning-point in American Track & Field; the NYAC were experimenting with new forms of competition and new Laws were being written, creating, in effect, a new focus for the sport in America and, eventually, internationally.

Nevertheless, none of the athletes in the NYAC’s Winter Meeting had any had real drawing power in 1879. That would soon change but, sadly, the organisers, and those who did turn up to watch, did not know that one of the greatest runners of all time had entered the 220yds and 440yds events - being given a handicap of 8yds and 15yds respectively - and as he had run his first race only two months earlier, he was still unknown to almost everyone. He was slightly built, only 5ft 7¾ tall (152.4cms), and weighed 8st 2lbs. (114lbs.; 51.71kg). His name was L.E. (Lon) Myers, and he ran for the Knickerbocker Yacht Club, and was not quite 21 years old.

We should spare a thought, perhaps, for Augustus Imbrie Burton from Columbia College, who was off scratch in that 440yds, and so gave Lon Myers a 15yds start. Before the end of the year Myers had secured his fame by being the first man to run inside 50s for the 440yds. Burton had run 56s a few months earlier, admittedly on a heavy track, and he also ran 220s and 880s for Columbia College. Augustus Burton was a sports enthusiast who also refereed football matches but, unlike Lon Myers, he was not to find fame in athletics. He went into medicine, graduating from Belleview Hospital Medical College, New York, in 1888, but he was probably noted for being a sharp dresser, for he applied for, and received (in 1883), a patent from the US Patent Office for a device that held your necktie knot (or cravat) to the your collar. But he will never have forgotten the day in 1879 when he gave Lon Myers a 15yds start in a 440yds race. Sadly, he died in his early 30s.

Lon Myers went on to win 28 national championships before retiring in 1885, and set World Records at 11 different distances, holding every American record from 50yds to 1-Mile. In 1886 he began racing as a professional and ran some high-profile races against Walter George. He died at the age of 41.

The text:

The Athlete Vol., No.1 comprises a single folded sheet that resulted in four printed pages, each about 10.5 x 14 inches; so, a little smaller than the Daily Mail. Its mast-head contains images of tug of war, boxing, race-walking, running, and rowing, and so reflected the interests of the New York Athletic Club, and not the events of the January 1879 Winter Meeting.

Curiously, however, the Meeting itself contained events that were not in the programme. Light, Middle, and Heavyweight sparring took place, starting at 7pm. Perhaps this was their way of getting around the problems of the previous year; the meeting was advertised to start at 8pm, and so the sparring (starting at 7.00) wasn’t part of the Meeting at all! There was also fencing “for the amateur championship”. Grafulla’s 7th Regiment Band played throughout the evening.

The page layout of the programme divides each page into three columns, and, on three of the four pages, only the central column gave any athletic information; the rest is given over to advertising which takes up about two thirds of all the space. There are advertisements for pedometers, billiard tables, pen nibs, cigars, bicycles (penny-farthings of course), jewellers, cigarettes (one of which dominates the middle two pages), a gym, boxing rooms, two academies of physical culture, glue, a photographer, and several athletics goods suppliers, one of which was a manufacturer and distributer of rowing machines and other indoor fitness equipment; their “Parlor Rowing Machine” is illustrated with an engraving of a woman rowing in her living room! One jeweller's advertisement announces that its products were particularly suitable for members of New York’s “Secret Societies” - and one wonders what links the members of the NYAC had with them too.

So, advertising revenue paid for the cost of the printing, and the advertisers would have been attracted by the promise of a good crowd. In the event, 6,000 went to watch the second day, but the first day, made up primarily of heats, would have attracted far fewer paying customers.

The crowd-pleasers were the Tug-of-War events, of which there were two on Day 1 - an “Amateur Tug of War” and the “7th Regiment Tug of War”; both were 10-a side events, and both had their finals the next day. The 7th Regiment was a New York State Militia, and had been part of New York’s National Guard during the American Civil War, and their Regimental Band (Grafulla's)played throughout the evening (see above) - many NYAC members were also part of the 7th Regiment, and there were close links between the two.

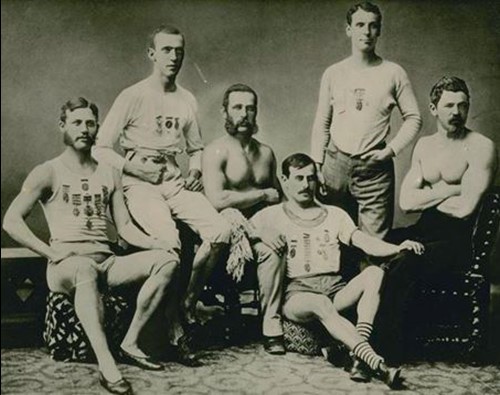

The importance of Tug-of-War events on the programme reflects the importance of the event in athletics of the late 19th and early 20th century Track & Field, not only in the USA, but in Britain too. In these early years of athletics, however, Tug-of-War was not as separate from the rest of the athletics programme as it now seems. The athletes in the Heavy Events (the throws) often took part in Tug of War events, as did athletes in other events. We can see this with the New York Athletic Club’s Tug-of War team that got eliminated in their “trial pull” on Friday evening. Their captain was William B Curtis (the famous Father Bill Curtis) who was nearly 42 years of age but had been a founder member of the NYAC and an outstanding sprinter, thrower, lifter, swimmer, rower and all-round strong man. Also in the team was Harry E Buermeyer who, too, was a founder member of the NYAC, and was nearly 40; but he had been a sprinter, shot putter, gymnast, rower, boxer, and weight-lifter. Other members of the NYAC’s Tug of War team were William McCredy, who was a walker, Frank J Kilpatrick, who was a Triple Jumper; and two of the substitutes were Daniel M. Stern, a walker, and H. Edwards Ficken, who was a hurdler. There was no sharp dividing line between those in the Tug of War teams and those in the other athletic events. Three of them can be seen in this picture from 1873 -

Father Bill Curtis is third from the left, Daniel Stern is fourth from the left, and Harry Beurmeyer is on the far right.

The Second Day (Saturday 4th January). The programme for the second day is listed on the back page of this programme, but there were also additional events - one, a 10-Mile bicycle race, was run as two heats. Once again, however, it was Tug-of-War that got the crowd going. There were three Tug-of-War events in the evening - an “International” event with four teams of working men - one, between “an Irish team of Greenpoint workingmen”, and “a team of American lightermen”, which the Irish team won in 35¼s. (lightermen unloaded cargo from smaller barges and then took them to the quayside in New York Harbour and elsewhere for unloading. They also transported goods from one dock to another.) The second was between “a team of Greenpoint Lightermen” and “a team of New York Irishmen”, which the New York Irishmen won in 23¼s. The final was, therefore, between two Irish teams, which proved to be so evenly matched that they barely moved for 15 minutes, at which time the Irish men from Greenpoint were judged to have a “slight advantage”.

The next Tug-of-War event was the final of the 7th Regiment event, which was between Company C and Company K, and which was won by Company K in a little over 2mins.

The final of the Amateur event was left as the grand finale of the evening and was between the Scottish-American Athletic Club and the Empire City Gymnasium. This is odd, because, according to the programme, these two teams faced each other in the “First Trial” the previous evening, with the losers being eliminated. Presumably the Trials on Friday night did not go according to programme, and so they met in the final. Going into the final, the Scottish-American team were unbeaten, and thought to be unbeatable, but it was a tense affair, with the pull going the whole 15mins; and with an excited crowd shouting and screaming, the Empire City Gym held on to win by a narrow margin. So tense was it, and so keyed up were the competitors, that the two teams almost came to blows at the end; or, as The World politely reported - “there was the prospect of a disturbance.”

Peter Radford / August 2018

Bibliographic details:

Title:

The Athlete Vol., No.1., 1879

Publisher:

D. D. Comes

Place of Publication:

New York

Date of Publication:

1879

BL Catalogue:

None

"An Athletics Compendium" Reference:

None